On the first day of First Grade, my mother got me up. We ate breakfast. I dressed in the garments she had laid out for me. My father kissed me on the top of my head. Out the door he went to work and only moments later out the door my mother and I went to school. I liked the notion of school. I knew how to read beyond my grade level. I loved books. Besides, I had the four pennies in my pocket that were required for chocolate milk at morning recess. I loved chocolate milk.

We found the room easily enough, what with all the signage. Mrs. Tidwell was clearly a serious woman but seemed amiable enough. She directed me to a seat on the front row, which suited me just fine.

The desks were rather curious affairs. They were designed for two students., with the students seated side-by-side facing forward. The desk top would be shared. Two little cubby holes for your books and personal items were positioned under the desktop between the two seats. You took one, your desk mate took one.

I got to the desk first and was instructed by Mrs. Tidwell to put my books in the top slot and to sit quietly. Class would begin shortly. My mother waved good-bye. She wanted to kiss me, I could tell. But I had already made it clear to her in the car that this was not going to happen in the hallway of Will Rogers Elementary. Not going to happen.

There I was at my desk feeling happy and pretty good about things in general. I had a congenial teacher and had been placed right at the head of the class where I could involve myself in things. At about five minutes into my academic career, we were off to a smooth start.

The storm cloud came in the form of one Theodore Ulysses Wilcox Dorsburg, my desk mate. I don’t think we even acknowledged each other’s presence as class got started. I did not recognize him. He did not seem like the oil field and ranching stock I came from. He seemed scrubbed, groomed, and dressed for a part in an English play. My interest folded.

Mrs. Tidwell closed the door to the classroom and came around behind her desk. She gave a word or two of greeting and commenced instructions regarding what would and would not be tolerated in terms of class behavior. Then she put us straight to work by instructing us to print our first and last names on the little green index cards she passed out.

I printed my name in what I thought an exemplary manner. (It probably was. I had a pretty good hand.) Then we were instructed to put our cards at the top of the desk. She said she would be by to pick them up presently.

Theodore looked over at my card and asked in a brash manner, “What’s your name?” His accent matched his dress and appearance: too formal by half. I did not like his tone. I didn’t know this strange fellow and we hadn’t even said hello. Where did he come off asking a question wrapped in such an unpleasant fragrance?

Nevertheless, I took a shot at civility. I looked at him coolly and spoke my first name. Theodore twisted his face into a condescending grimace and said: “No, what’s your last name?”

I have almost no tolerance for arrogance, and that’s the trail Theodore launched out onto with enthusiasm. I answered him in an icy tone, “Pharis.”

“You spell your name wrong,” he smirked. “It’s supposed to be with an F. You know F as in the F sound. Fire. Get it?”

I considered this for a moment. “No, P as in Phone.”

“Crap, you are stupid,” he said with disgust and turned his head back toward the front of the room.

I remember I glared at him, wondering where he came off telling me how to spell my name. I remember Mrs. Tidwell admonished us to be quiet, and Theodore looked at her like the leading candidate for teacher’s pet.

I’ll never be sure exactly how the decision was made. All I know is that next thing, I knocked Theodore out of his chair and on to the floor with one serious whack to his jaw. The whole room froze. Theodore looked up at me in uncomprehending befuddlement. Then his head eased back onto the floor and his eyes rolled like he was a half inch from a concussion.

Mrs. Tidwell bolted from her desk and presented herself at a device on the wall between the blackboard and the pencil sharpener. She spoke into a kind of phone insisting that the vice principal and the school nurse come to her room IMMEDIATELY.

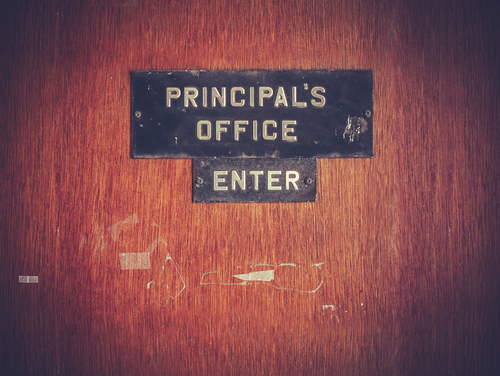

Now I am not going to pretend to you that I did not think there wouldn’t be consequences from me knocking Theodore completely out of his chair onto the floor. But Mrs. Tidwell’s reaction seemed a bit over the top to me. I had had warnings from older cousins who went to Will Rogers: do not get anywhere near even attracting the attention of the Principal or Vice Principal. And here was Mrs. Tidwell, asking for them IMMEDIATELY.

Quicker than you can say “Jack Flash” the authorities were at the door of the classroom and I was in custody, being transported to the office. Before we left the room, Mr. Baker took note of Mrs. Tidwell’s understanding of the encounter between Theodore and me. Once we reached the office Mr. Baker asked for my rendition of events, but my explanation did not move the vice principal to think that I had a future in conflict resolution.

Very shortly, he had my father on the phone, explaining that there had been some problems with my launch into public education. Mr. Baker handed me the phone. “Your Father wants to talk to you” he said.

I got on the phone and Dad said “Jiminy Christmas, your mother dropped you off at school at 8 a.m. this morning, and I’m getting a call from the principal’s office at 8:15. This is not a good start.”

What was I supposed to say? I knew it wasn’t a good start. I also knew I couldn’t and wouldn’t take crap from buffoons like Theodore Ulysses Wilcox Dorsburg. I didn’t say this. Instead, I said, “Yes sir.”

He took a breath. He asked if I had done what Mr. Baker reported.

“Yes, sir.”

He informed me that I would take whatever punishment that would be forthcoming.

“Yes, sir.”

Fortunately, Mr. Baker concluded that he would give me a pass, since it was just the first day of school. He allowed that he would speak with Theodore too, and that we both had some settling in to do. He made it very clear that this was a one-time pass on punishment.

At supper my mother cried and wailed about how her reputation as a mother had been ruined by my behavior.

My father was a bit more pragmatic. “Son,” he said sternly, “life is going to be a rocky road if you have to deck every fellow who is less than civil to you.”